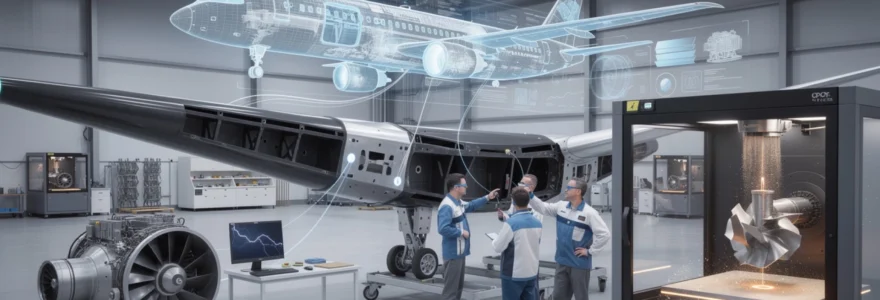

The aerospace industry stands at the precipice of a technological revolution, where cutting-edge materials, manufacturing processes, and digital technologies are fundamentally reshaping how aircraft components are designed, manufactured, and maintained. From the microscopic structure of carbon fibres to the macroscopic integration of artificial intelligence in predictive maintenance systems, modern aeronautical components embody decades of scientific advancement and engineering excellence. These innovations are not merely incremental improvements but represent quantum leaps in performance, efficiency, and sustainability that are enabling the next generation of aircraft to achieve unprecedented levels of safety, fuel efficiency, and operational capability.

The convergence of advanced materials science, additive manufacturing, sensor technology, and artificial intelligence is creating a new paradigm in aerospace engineering. Today’s aircraft components must withstand extreme temperatures, pressures, and stresses whilst maintaining structural integrity over decades of service. This demanding environment has driven the development of revolutionary solutions that push the boundaries of what’s possible in materials engineering and manufacturing precision.

Advanced composite materials revolutionising aircraft structural design

The transformation of aircraft structural design through advanced composite materials represents one of the most significant innovations in modern aerospace engineering. These materials have fundamentally altered the weight-to-strength ratio paradigm that has governed aircraft design for decades, enabling manufacturers to create lighter, stronger, and more fuel-efficient aircraft than ever before possible.

Modern composite materials combine high-performance fibres with sophisticated matrix systems to create structures that outperform traditional metallic components in virtually every measurable parameter. The strength-to-weight ratio of advanced composites can exceed that of aluminium by factors of three to four, whilst offering superior fatigue resistance and corrosion immunity. This performance advantage has made composites indispensable in contemporary aircraft design, where every kilogram of weight savings translates to measurable improvements in fuel efficiency and operational economics.

Carbon fibre reinforced polymer (CFRP) integration in boeing 787 dreamliner fuselage construction

The Boeing 787 Dreamliner represents the pinnacle of CFRP integration in commercial aviation, with the aircraft’s fuselage constructed as a single-piece composite barrel rather than the traditional aluminium panels and frames approach. This revolutionary construction method eliminates thousands of fasteners and joints, creating a seamless structure that offers superior pressure containment and fatigue resistance.

The CFRP fuselage sections are manufactured using automated fibre placement technology, which precisely controls fibre orientation and resin content throughout the structure. This level of manufacturing precision enables the creation of tailored stiffness zones within the fuselage, optimising structural performance for specific load paths whilst minimising overall weight. The result is a 20% reduction in structural weight compared to equivalent aluminium construction, contributing significantly to the aircraft’s industry-leading fuel efficiency.

Thermoplastic matrix systems for enhanced recyclability in airbus A350 wing components

Airbus has pioneered the use of thermoplastic matrix composites in critical wing components of the A350, representing a significant advancement in sustainable aerospace manufacturing. Unlike traditional thermoset composites, thermoplastic matrix systems can be remelted and reformed multiple times without degradation of mechanical properties, enabling complete recyclability at the end of the component’s service life.

The thermoplastic composite wing components demonstrate superior damage tolerance and impact resistance compared to thermoset equivalents. The ability to locally heat and reform thermoplastic composites also enables innovative repair techniques, where damaged sections can be thermally welded rather than requiring complex bonded patch repairs. This characteristic reduces maintenance costs whilst extending component service life, creating both economic and environmental benefits.

Ceramic matrix composites (CMCs) in general electric GE9X engine hot section applications

The development of ceramic matrix composites for engine hot section applications represents a breakthrough in high-temperature materials technology. General Electric’s GE9X engine incorporates CMC components in the combustor liner and turbine shrouds, where operating temperatures exceed 1,400°C. These components must withstand not only extreme temperatures but also rapid thermal cycling and aggressive chemical environments.

CMC materials offer exceptional temperature capability whilst maintaining significantly lower density than superalloy alternatives. The silicon carbide fibre reinforced silicon carbide matrix system used in the GE9X enables turbine operating temperatures approximately

50–150°C higher than previous-generation engines while reducing component weight by up to 30%. This combination of higher turbine inlet temperatures and lower mass directly improves thermal efficiency, translating into reduced fuel burn and lower CO2 emissions. In practice, CMCs allow engine designers to push closer to theoretical thermodynamic limits without incurring the cooling penalties traditionally associated with nickel-based superalloys.

From a lifecycle perspective, CMC components in the GE9X also contribute to reduced maintenance requirements. Their superior oxidation resistance and creep performance at elevated temperatures mean fewer inspections and longer on-wing times, which is particularly valuable in high-utilisation long-haul operations. As manufacturing techniques mature and costs decrease, we can expect broader deployment of CMCs across turbine stages, combustor hardware, and even nozzle guide vanes in future aero engines.

Hybrid metal-composite joints using selective laser melting for weight optimisation

One of the persistent challenges in aircraft structural design is efficiently joining metallic and composite substructures without compromising load transfer or durability. Hybrid metal-composite joints produced via selective laser melting (SLM) offer a powerful solution. With SLM, engineers can build metallic interface features layer by layer, tailoring geometries to match composite layups and distribute loads smoothly, much like roots spreading through soil rather than a single rigid peg.

By integrating textured surfaces, lattice structures, and mechanically interlocking features directly into the additively manufactured metal interface, these hybrid joints significantly improve shear load transfer and peel resistance when bonded to CFRP or thermoplastic laminates. This allows designers to reduce traditional bolted hardware, cut local reinforcement plies, and ultimately remove kilograms of non-value-adding mass from the airframe. For operators, this weight optimisation translates into tangible fuel savings over the aircraft’s service life.

In addition, SLM-produced joints enable rapid iteration and customisation. If you are developing a new aerostructure, you can adjust joint topology in the CAD model and print a revised prototype in days rather than weeks. This design agility accelerates certification testing and supports more ambitious structural concepts, such as integrated wing-fuselage fairings and morphing control surfaces.

Nanoenhanced composites with graphene integration for lightning strike protection

Lightning strike protection (LSP) is a critical design requirement for composite airframes, which are inherently less conductive than aluminium. Traditionally, metallic meshes or foils are co-cured into the outer plies to dissipate strike energy, but these solutions add weight and can complicate repairs. Nanoenhanced composites incorporating graphene and other carbon-based nanomaterials are changing this paradigm by embedding conductivity directly into the matrix system.

By dispersing graphene nanoplatelets within the resin, manufacturers can create composite skins with significantly improved in-plane and through-thickness electrical conductivity. This allows lightning currents to spread more uniformly, reducing localised heating and delamination risk. Because graphene is extremely light and mechanically robust, the additional mass is minimal compared with traditional copper meshes, yet the LSP performance can equal or exceed legacy solutions.

Beyond lightning protection, these nanoenhanced laminates can also support self-sensing capabilities. Changes in electrical resistance under strain or damage can be monitored to infer structural health, effectively turning the aircraft skin into a distributed sensor network. For airlines, this opens the door to faster post-strike inspections and more accurate decisions on whether components can safely return to service.

Additive manufacturing technologies transforming aerospace component production

Additive manufacturing (AM), often referred to as industrial 3D printing, is radically transforming how modern aeronautical components are designed, certified, and produced. Instead of machining away material from a billet or forging, AM builds parts layer by layer, enabling complex geometries that would be impossible or prohibitively expensive using conventional methods. For aerospace, where every gram counts and internal flow paths are critical, this design freedom is especially valuable.

Crucially, AM is not just about complexity; it is about functional integration. Components that once required multiple parts, fasteners, and sealing interfaces can now be consolidated into a single printed part. This reduces assembly time, potential leak paths, and overall part count across the aircraft. As certification bodies refine standards for additively manufactured flight hardware, we are seeing a rapid expansion from non-critical brackets into engine components, environmental control system manifolds, and even primary structural fittings.

Powder bed fusion techniques for titanium alloy turbine blade manufacturing

Powder bed fusion (PBF) processes, such as selective laser melting (SLM) and laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF), have proven particularly effective for producing titanium alloy turbine blades and vanes. Titanium’s high strength-to-weight ratio and corrosion resistance make it ideal for fan and compressor components, but traditional subtractive manufacturing often results in high material wastage and lengthy lead times. With PBF, titanium powder is selectively melted by a laser, forming each cross-section with micron-level precision.

This approach allows designers to introduce optimised internal cooling channels, weight-saving lattice structures, and complex aerodynamic profiles that are simply unattainable with cast or forged parts. For example, serpentine cooling passages with varying cross-sections can be embedded close to the blade surface, improving thermal management while minimising coolant flow penalties. In practice, this leads to blades that are both lighter and better able to withstand high-cycle thermal and mechanical loading.

From a supply chain perspective, PBF can shorten development cycles and reduce inventory. Need a design tweak to accommodate a new engine operating profile? You update the digital model and print the next iteration without retooling. For low- to medium-volume production, such as business jet engines or military programmes, this design agility and on-demand production model can be especially attractive.

Direct energy deposition systems in Rolls-Royce trent engine repair applications

While PBF excels at net-shape production, direct energy deposition (DED) technologies shine in repair and feature addition on existing hardware. In DED, focused energy sources—typically lasers or electron beams—create a molten pool on the component surface into which metal powder or wire is fed. Rolls-Royce and other engine OEMs are increasingly using DED to repair high-value Trent engine components, extending their lifespan and reducing total lifecycle cost.

For example, worn or damaged tip sections of turbine blades can be rebuilt by depositing compatible superalloy material, followed by precision machining back to the required profile. This process can restore aerofoil geometry and tip clearances without scrapping the entire blade, which is particularly valuable given the high cost and long lead time of single-crystal superalloy components. In some cases, DED also allows design improvements to be retrofitted, such as adding wear-resistant coatings or modified seal features.

If you are responsible for engine maintenance planning, DED-based repair strategies can significantly change your cost models. Instead of viewing blades and vanes as disposable items, you can plan for multiple repair cycles, supported by digital records of material deposition, heat input, and inspection results. This integration of additive repair data into the engine’s digital twin further enhances predictive maintenance accuracy.

Electron beam melting (EBM) for complex geometry heat exchanger production

Electron beam melting (EBM), another powder bed process, is particularly well-suited to producing complex titanium heat exchangers and structural components. Operating in a high-vacuum environment, EBM reduces contamination risk and allows for higher build temperatures, which helps relieve residual stresses during fabrication. This is especially important for thin-walled, intricate geometries that could otherwise distort or crack.

Next-generation aerospace heat exchangers often require highly complex internal flow networks to manage thermal loads in compact spaces—for example, in engine oil cooling, environmental control systems, or power electronics thermal management. EBM enables designers to create lattice-supported channels, variable wall thicknesses, and integrated mounting lugs in a single monolithic build. The result is a component that resembles an organic structure more than a traditional machined block, yet delivers superior heat transfer and pressure drop performance.

From a sustainability standpoint, EBM’s material efficiency is also attractive. Powder reuse strategies, combined with reduced machining scrap, help lower the embodied energy of each component. As environmental performance becomes a key differentiator in aircraft development programmes, such manufacturing efficiencies will play an increasingly central role.

Multi-material 3D printing for integrated electronic component housing

Looking beyond metallics, multi-material AM systems are opening new possibilities for integrated electronic housings and avionics enclosures. These printers can deposit structural polymers, conductive inks, and even embedded passive components in a single build process, effectively blurring the lines between structure and electronics. Imagine an avionics box where the enclosure itself provides EMI shielding, integrated wiring pathways, and thermal management features without separate brackets, looms, or heat sinks.

Such integrated housings can reduce part count, assembly steps, and wiring complexity, which are all perennial cost drivers in aircraft electrical systems. They also support more flexible layouts: as you redesign a circuit board, you can adjust the geometry of the housing and its internal channels simultaneously, ensuring optimal fit and thermal performance. In safety-critical aerospace environments, this tight coupling between mechanical and electrical design can significantly improve reliability.

However, multi-material AM in aeronautical applications also introduces new challenges in qualification and repair. Different materials may age or respond to temperature cycling in distinct ways, so thorough environmental testing and clear maintenance procedures are essential. As standards evolve, we can expect to see these hybrid printed assemblies move from test rigs and secondary systems into primary flight hardware.

Smart sensor integration and structural health monitoring systems

As aerostructures have grown more advanced and less visually accessible, the aerospace industry has increasingly turned to smart sensor integration and structural health monitoring (SHM) to maintain safety and availability. Rather than relying solely on scheduled inspections and conservative lifing assumptions, modern aircraft can continuously monitor their own condition, much like wearable health trackers for humans. This shift from reactive to predictive maintenance is one of the defining trends in modern aeronautical components.

By embedding sensors directly into wings, fuselages, and critical mechanical assemblies, engineers can capture data on strain, vibration, temperature, and damage events in real time. When combined with advanced analytics and machine learning, this data supports condition-based maintenance, where interventions are triggered by actual component health rather than calendar time or flight hours. For operators, the benefits include reduced unscheduled downtime, optimised maintenance intervals, and extended asset life.

Piezoelectric transducers for real-time crack detection in wing spars

Piezoelectric transducers are at the heart of many SHM systems designed to detect cracks in critical load-bearing elements such as wing spars and fuselage frames. These devices can act as both actuators and sensors, emitting guided ultrasonic waves through the structure and listening for reflections that indicate defects. Think of it as sonar for metal and composite components, where subtle echoes reveal hidden flaws long before they become visible.

In a typical installation, an array of piezoelectric patches is bonded along the spar. During flight or at set intervals on the ground, the system excites the structure with high-frequency signals and analyses the returning waveforms. Deviations from baseline signatures can be correlated with crack initiation, corrosion, or disbonding, allowing maintenance teams to localise and quantify damage without disassembly. This approach is particularly valuable in areas that are difficult or impossible to access visually.

For designers, integrating these transducers early in the development process is crucial. You must consider wiring routes, data acquisition hardware, and redundancy strategies from the outset. When implemented well, piezoelectric-based SHM can support life extension programmes and provide regulators with high-confidence evidence that structures remain within safe operating limits.

Fibre bragg grating sensors in composite laminate strain monitoring

Fibre Bragg grating (FBG) sensors provide another powerful tool for monitoring strain and temperature in composite laminates. These optical sensors consist of periodic variations in the refractive index along an optical fibre, which reflect specific wavelengths of light. As the fibre is strained or heated, the reflected wavelength shifts, providing a direct measure of the local mechanical or thermal state.

Because FBGs are so small and lightweight, they can be embedded between composite plies during layup with minimal impact on structural performance. A single fibre can host dozens of gratings along its length, enabling distributed sensing across a wing skin or tailplane. Unlike traditional electrical strain gauges, FBGs are immune to electromagnetic interference and can operate reliably in harsh environments, including cryogenic conditions for space applications.

If you are working with large composite structures, FBG-based monitoring can help validate design models, verify manufacturing quality, and track in-service load spectra. Over time, the accumulated data can feed back into improved design allowables and more accurate fatigue life predictions, reducing conservatism without compromising safety.

Wireless sensor networks for distributed temperature monitoring in engine nacelles

In high-temperature zones such as engine nacelles and bleed air ducts, wireless sensor networks are gaining traction for distributed temperature and pressure monitoring. Running extensive wiring harnesses in these environments adds weight, complexity, and potential failure points. By contrast, compact sensor nodes with low-power radios can transmit data to a central gateway, simplifying installation and maintenance.

Modern wireless sensors leverage robust communication protocols, energy harvesting, and advanced encryption to operate reliably in the harsh electromagnetic and thermal environment around jet engines. They can track local hot spots, detect insulation degradation, and provide early warnings of abnormal conditions that could precede nacelle fires or bleed air leaks. For engine OEMs and airlines, this improved situational awareness supports quicker troubleshooting and safer operations.

Of course, wireless systems in safety-critical aircraft zones must meet stringent certification requirements. You need to demonstrate not only that the sensors perform as intended, but also that their transmissions do not interfere with other avionics. As standards mature, we are likely to see even broader deployment of these networks, especially in retrofit programmes where re-wiring is impractical.

Machine learning algorithms for predictive maintenance in landing gear assemblies

Landing gear assemblies are among the most highly loaded and safety-critical mechanical systems on an aircraft, yet traditional maintenance approaches often rely on conservative overhaul intervals. By applying machine learning algorithms to sensor data from shock struts, bogies, and actuators, operators can move towards truly predictive maintenance strategies. Instead of replacing components “just in case,” you replace them when the data indicates they are nearing the end of their useful life.

Key data sources include vibration signatures during taxi and landing, hydraulic pressure traces, extension and retraction times, and even audio recordings analysed for anomalies. Machine learning models trained on historical failure cases can identify subtle patterns that human analysts might miss—much like a seasoned mechanic who “hears” something wrong, but with the added rigour of statistical validation. These models then generate health scores or remaining useful life estimates for each gear component.

For fleet managers, the practical outcome is fewer unexpected AOG (aircraft on ground) events and more efficient scheduling of heavy maintenance checks. However, building trustworthy models requires high-quality labelled data and close collaboration between data scientists, engineers, and maintainers. You must also manage change carefully: replacing traditional rule-based maintenance regimes with AI-driven recommendations is as much a cultural shift as a technical one.

Next-generation propulsion system components and materials

Propulsion is at the centre of aviation’s push toward greater efficiency and lower emissions, and modern aeronautical components are evolving rapidly to support this transition. From ultra-high bypass ratio turbofans to open-rotor concepts and hybrid-electric demonstrators, next-generation engines demand materials and architectures that can handle higher temperatures, larger fan diameters, and more integrated nacelle systems. The result is a new ecosystem of advanced blades, casings, and accessory components designed specifically for these propulsion architectures.

Beyond CMCs in hot sections, we are seeing wider adoption of geared turbofan architectures that decouple fan and core speeds, enabling larger, slower-spinning fans with thinner, composite-rich blades. These blades often combine titanium leading edges with CFRP or thermoplastic composite bodies, leveraging the impact resistance of metal and the weight savings of composites. In parallel, fan cases and inlet structures are increasingly made from carbon composites with integrated acoustic liners, reducing both weight and community noise.

Looking further ahead, hydrogen and hybrid-electric propulsion concepts introduce new material challenges. Cryogenic hydrogen storage tanks require multi-layer composite structures with excellent permeation resistance, while high-voltage electrical machines demand advanced insulation systems and thermally conductive dielectrics. As you evaluate propulsion options for future platforms, the interplay between novel fuels, electrical architectures, and structural materials will become a central design consideration rather than an afterthought.

Digital twin technology and virtual component testing methodologies

Digital twin technology has moved from buzzword to practical engineering tool in modern aerospace programmes. A digital twin is a high-fidelity virtual representation of a physical component or system, continuously updated with real-world data from sensors and maintenance records. For aeronautical components, this means that every engine, wing, or landing gear leg can, in principle, have its own evolving virtual counterpart that reflects its actual operating history.

In the design phase, digital twins enable extensive virtual testing of components under a wide range of simulated conditions—thermal loads, gusts, bird strikes, or lightning events—before any hardware is built. Coupled fluid-structure interaction models, high-resolution finite element analysis, and computational fluid dynamics can be orchestrated to explore design spaces that would be impractical to test physically. This reduces the number of prototypes required and helps you converge on robust, certifiable designs faster.

Once the aircraft enters service, operational data flows back into the twin, allowing engineers to validate assumptions, update degradation models, and refine maintenance recommendations. For example, if in-service strain data from wing sensors indicates higher-than-expected loads on specific flight routes, the twin can be updated to reflect this, and fatigue predictions adjusted accordingly. Over an entire fleet, these insights can support service bulletins, design tweaks, or updated operating procedures that enhance safety and reduce total cost of ownership.

Sustainable manufacturing processes and bio-based aerospace materials

Sustainability has become a defining constraint—and opportunity—in the development of modern aeronautical components. It is no longer sufficient for a part to be light and durable; it must also be produced, operated, and retired in ways that minimise environmental impact. This shift is driving both cleaner manufacturing processes and the exploration of bio-based materials that can complement traditional aerospace alloys and composites.

On the manufacturing side, process optimisation efforts focus on reducing energy consumption, scrap rates, and hazardous chemical use. Additive manufacturing, as discussed earlier, inherently supports material efficiency by using only what is needed. Closed-loop coolant systems, water-based cleaning processes, and improved cure cycles all contribute to lower embodied carbon in finished components. Some OEMs now track and report lifecycle emissions for key parts, allowing airlines to factor embedded carbon into fleet procurement decisions.

In parallel, research into bio-based resins and natural fibre reinforcements aims to create composite materials with reduced reliance on fossil-derived feedstocks. While such materials are unlikely to replace high-performance carbon/epoxy in primary structures in the near term, they are already finding applications in interior panels, fairings, and secondary components where extreme mechanical properties are less critical. For example, flax or hemp fibres combined with bio-sourced resins can deliver adequate stiffness and impact resistance for interior monuments, while offering improved end-of-life recyclability or compostability.

For aerospace suppliers and manufacturers, staying ahead in this area means engaging early with sustainability-focused R&D, investing in greener production technologies, and collaborating across the value chain—from raw material providers to recyclers. As regulatory pressure and passenger expectations continue to rise, the innovations that define modern aeronautical components will increasingly be judged not only by how well they perform in flight, but also by how responsibly they are made and managed across their entire lifecycle.