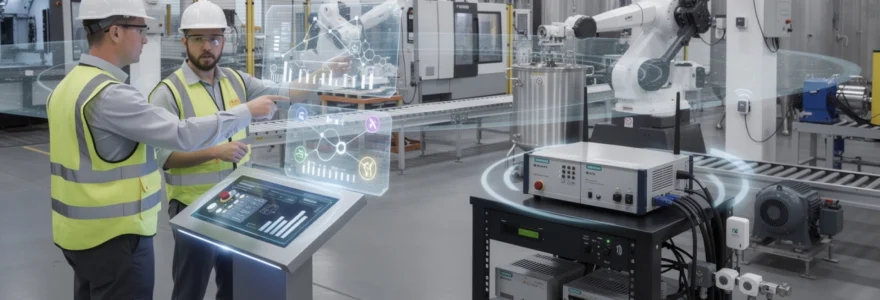

Industrial environments are undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the rapid adoption of wireless technologies that promise unprecedented flexibility, efficiency, and intelligence. From sprawling refineries to compact manufacturing cells, wireless communication systems are dismantling the constraints of traditional wired infrastructures, enabling real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and autonomous operations that were once considered impractical or prohibitively expensive. The elimination of costly cabling, combined with the ability to deploy sensors in previously inaccessible locations, has opened new frontiers in plant asset management and operational optimisation. As industries grapple with the demands of digital transformation and Industry 4.0 initiatives, wireless technology has emerged not merely as a convenience, but as a strategic imperative that fundamentally reshapes how industrial systems communicate, adapt, and evolve.

Wireless protocol standards driving industrial automation: ISA100.11a, WirelessHART, and 5G URLLC

The industrial automation landscape relies on a diverse ecosystem of wireless protocol standards, each designed to address specific operational requirements and use cases. Unlike consumer-grade wireless systems, industrial protocols must deliver deterministic performance, withstand harsh electromagnetic environments, and maintain connectivity across vast physical distances whilst supporting hundreds or thousands of devices simultaneously. The standardisation efforts have crystallised around several key technologies, with ISA100.11a, WirelessHART, and 5G Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communications (URLLC) emerging as the dominant frameworks for mission-critical applications.

Selecting the appropriate protocol requires careful consideration of factors including latency requirements, network scalability, integration with existing control systems, and long-term vendor support. Many industrial facilities implement multiple wireless technologies simultaneously, each serving distinct operational layers—from field-level instrumentation to enterprise-wide monitoring systems. This heterogeneous approach necessitates robust gateway infrastructure and careful spectrum management to prevent interference and ensure reliable coexistence.

Isa100.11a Time-Synchronised mesh networks for process control applications

ISA100.11a represents a comprehensive wireless networking standard specifically engineered for process automation and control. Developed by the International Society of Automation (ISA), this protocol operates in the 2.4 GHz ISM band and employs a time-synchronised mesh architecture that provides multiple redundant communication paths between field devices and control systems. The standard supports Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA) combined with frequency hopping spread spectrum techniques, delivering predictable latency and exceptional reliability even in electromagnetically noisy industrial environments.

One of the distinguishing features of ISA100.11a is its protocol-agnostic design philosophy, which allows seamless integration with various industrial communication protocols including FOUNDATION Fieldbus, HART, Profibus, and Modbus. This interoperability extends the standard’s applicability across diverse industrial sectors, from chemical processing to power generation. The network can accommodate over 1,000 devices whilst maintaining deterministic communication cycles, making it particularly suitable for large-scale installations where traditional wired systems would be economically prohibitive or physically impractical.

The implementation of ISA100.11a requires careful site planning, including radio frequency surveys to identify potential sources of interference and optimal placement of backbone routers and field devices. The standard incorporates sophisticated channel blacklisting mechanisms that automatically avoid frequencies experiencing persistent interference, ensuring consistent network performance throughout the operational lifecycle. Security features include AES-128 encryption with key management protocols aligned with IEC 62443 requirements, providing robust protection against unauthorised access and data manipulation.

Wirelesshart field device integration and Self-Organising network architecture

WirelessHART extends the widely deployed HART protocol into the wireless domain, leveraging decades of industry familiarity with HART-based instrumentation. Ratified as IEC 62591, WirelessHART employs a self-organising mesh network topology that automatically establishes optimal communication routes and adapts to changing environmental conditions or device failures. This self-healing capability ensures continuous operation even when individual network nodes become unavailable due to battery depletion, physical obstruction, or equipment maintenance.

The protocol operates on IEEE 802.15.4 compatible radios in the 2.4 GHz band, utilising channel hopping across fifteen frequencies to mitigate interference and multipath fading effects common in industrial settings. Each communication cycle, or superframe

is divided into time slots, with each device following a schedule managed by the network manager to ensure deterministic, collision-free communication suitable for process monitoring and basic control tasks.

WirelessHART is particularly attractive for brownfield deployments, where a vast installed base of HART-enabled instruments already exists. Wireless adapters can be retrofitted to legacy devices, allowing plants to extend diagnostics, enable continuous condition monitoring, and add new measurement points without running additional cables. Although a single WirelessHART network typically supports around 250 devices, this capacity is sufficient for many unit operations and skids, especially when combined with multiple gateways across a site.

From an integration standpoint, WirelessHART gateways provide mapping to standard industrial protocols such as Modbus/TCP, OPC UA, and PROFINET, enabling seamless connectivity to DCS and SCADA systems. Security is handled through AES-128 encryption, device authentication, and session key rotation, reducing the risk of spoofing or eavesdropping on wireless sensor traffic. For operators seeking a low-risk entry point into wireless industrial communication, WirelessHART offers a mature, field-proven path with limited disruption to existing workflows.

5G Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency communications (URLLC) for Mission-Critical industrial operations

5G URLLC represents a step change for wireless industrial automation, targeting latency figures below 1 ms and reliability levels exceeding 99.999% for critical links. Unlike earlier cellular generations designed primarily for consumer broadband, 5G introduces network slicing, quality-of-service guarantees, and massive machine-type communications specifically geared towards industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) deployments. For applications such as motion control, high-speed robotics, and safety-related interlocks, these capabilities make 5G a compelling alternative or complement to wired fieldbuses.

In mission-critical scenarios, you can think of 5G URLLC as the wireless equivalent of a high-performance dedicated control network, but without the physical cable plant. Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs), mobile robots, and collaborative robots can receive deterministic control signals while streaming video and telemetry back to edge servers for AI-based decision-making. This is particularly powerful in large facilities, ports, and logistics hubs where continuous mobility is essential, and traditional Wi‑Fi roaming may introduce unacceptable jitter or packet loss.

Industrial adopters can choose between public 5G services managed by telecom operators and private 5G networks deployed on-site with dedicated spectrum (for example, in the 3.5 GHz band where regulations permit). Private 5G offers tighter control over security policies, coverage optimisation, and integration with existing OT networks, but requires upfront investment in core network components and radio infrastructure. Whichever deployment model you choose, careful radio planning, device certification, and cybersecurity hardening are vital to ensure that 5G URLLC lives up to its promise in demanding industrial environments.

Wi-fi 6E and private LTE networks in manufacturing facilities

While 5G often occupies the spotlight, Wi‑Fi 6 and Wi‑Fi 6E are rapidly becoming workhorses of industrial wireless connectivity. Wi‑Fi 6E extends Wi‑Fi 6 into the 6 GHz band, unlocking additional spectrum with less congestion than the legacy 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz ranges. This translates into higher throughput, lower contention, and more predictable performance for dense deployments of handhelds, tablets, engineering workstations, and non-critical IIoT devices. Features such as Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiple Access (OFDMA) and Target Wake Time improve efficiency and battery life for industrial clients.

Private LTE networks, often deployed using 4G/LTE technology in dedicated or shared spectrum, bridge the gap between traditional Wi‑Fi and full 5G implementations. They provide wider coverage, stronger mobility management, and carrier-grade security while maintaining relatively mature device ecosystems. In many plants, private LTE is used for outdoor areas, yard operations, and mobile workforce communications, while Wi‑Fi 6E covers indoor production halls and offices.

Designing a robust wireless fabric in manufacturing facilities often means combining these technologies under a unified management and security framework. For example, you might use Wi‑Fi 6E for engineering laptops and AR headsets on the shop floor, private LTE for forklifts and yard vehicles, and 5G URLLC (where available) for ultra-critical motion control. The challenge is less about choosing a single “best” technology and more about orchestrating a multi-layer wireless architecture that aligns with your latency, reliability, and mobility requirements.

Industrial internet of things (IIoT) sensor networks and edge computing infrastructure

As wireless technologies proliferate, the Industrial Internet of Things sensor network has become the nervous system of advanced factories and process plants. Thousands of distributed wireless sensors continuously measure vibration, temperature, flow, pressure, and energy usage, feeding data into edge computing platforms for real-time analysis. Instead of sending every data point to the cloud, edge devices filter, aggregate, and enrich information close to the source, reducing bandwidth consumption and enabling faster responses to changing process conditions.

In practice, an effective IIoT architecture combines different wireless technologies according to range, power, and data-rate requirements. Long-range, low-power networks connect remote assets such as storage tanks and pipelines; mid-range mesh networks cover plant-wide condition monitoring; and short-range solutions like Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) serve indoor positioning and local diagnostics. Edge gateways act as protocol translators and security anchors, bridging these heterogeneous sensor networks to higher-level SCADA, MES, and cloud analytics platforms.

This layered approach is what makes modern industrial systems genuinely “smart”. By combining wireless IIoT sensor networks with edge computing infrastructure, operators can implement advanced use cases such as closed-loop optimisation, machine learning at the edge, and autonomous workflows. The key is to design your network topology and compute placement with clear objectives in mind: which data must be processed in milliseconds, which can tolerate seconds or minutes, and which is best stored for long-term trend analysis.

Lorawan and NB-IoT connectivity for Wide-Area asset monitoring

LoRaWAN and Narrowband IoT (NB‑IoT) are purpose-built for low-power, wide-area networking (LPWAN) scenarios, where devices may be dispersed over many kilometres and transmit only small bursts of data. LoRaWAN typically operates in unlicensed sub‑GHz bands (such as 868 MHz or 915 MHz), allowing organisations to deploy private networks with their own gateways. NB‑IoT, by contrast, leverages licensed cellular spectrum managed by mobile network operators, offering strong coverage and roaming capabilities without requiring on-site base station infrastructure.

For industrial asset monitoring, these technologies shine in applications such as remote tank level measurement, pipeline cathodic protection monitoring, environmental sensing, and utility metering. Devices can operate for years on a single battery, dramatically reducing maintenance overhead. Data rates are modest—often only a few kilobits per second—but more than adequate for periodic telemetry, alarms, and status updates.

When deciding between LoRaWAN and NB‑IoT, you must weigh control versus convenience. Private LoRaWAN networks offer full ownership of infrastructure and data paths but require you to manage gateways, backhaul, and security. NB‑IoT simplifies deployment by using existing cellular networks, yet introduces dependencies on operators for coverage, SLAs, and long-term pricing. In many industrial ecosystems, both coexist: LoRaWAN for on-site or campus-wide monitoring, and NB‑IoT for geographically dispersed assets beyond the plant fence line.

Bluetooth low energy (BLE) beacons for indoor positioning and condition monitoring

Bluetooth Low Energy has evolved far beyond its original role of connecting headsets and consumer gadgets. In industrial environments, BLE beacons and tags are now central to indoor positioning systems, personnel tracking, and proximity-based safety applications. Because BLE radios are inexpensive and power-efficient, they can be embedded in tools, pallets, work orders, and even personal protective equipment to provide real-time location and status information.

Indoor positioning with BLE typically relies on a network of fixed beacons or access points that receive signals from mobile tags. Using received signal strength or more advanced methods such as angle-of-arrival, software platforms calculate approximate positions, often with accuracy in the 1–3 metre range. This is sufficient for many use cases: locating critical assets, guiding technicians to the right machine, or enforcing geofencing policies in hazardous zones.

BLE is also used for local condition monitoring, for example by embedding BLE sensors in rotating equipment where wiring is impractical. Maintenance staff can walk through an area with a tablet or smartphone and automatically collect vibration, temperature, or operating hours data from nearby assets. In this sense, BLE acts as a digital stethoscope, giving you insight into the health of equipment that would otherwise remain a blind spot.

Edge gateway devices: siemens SCALANCE, cisco industrial routers, and moxa UC series

Edge gateways are the linchpin connecting diverse wireless IIoT devices to higher-level control and analytics platforms. Products such as Siemens SCALANCE industrial routers, Cisco Catalyst IR and ISR series, and Moxa UC edge computers are designed to operate in harsh environments while supporting a wide variety of interfaces and protocols. They often combine Ethernet, Wi‑Fi, cellular, serial, and fieldbus connectivity in a single ruggedised platform, simplifying network architecture in complex plants.

Beyond basic routing, modern edge gateways host containerised applications, data brokers, and security services. You might run OPC UA servers, MQTT brokers, or machine-learning inference engines directly on the gateway, enabling real-time analytics and local decision-making without depending on a remote cloud. For latency-sensitive applications—such as anomaly detection on a packaging line—this ability to process data on-site can make the difference between a graceful intervention and a costly unplanned shutdown.

From a practical perspective, selecting an edge platform should involve more than just checking protocol support. You need to consider lifecycle support, cybersecurity features (secure boot, TPMs, certificate management), remote management capabilities, and integration with your existing IT/OT toolchain. Treat the gateway as both a network device and a compute node; its role in your architecture will grow over time as more functions migrate from central servers to the edge.

Time-sensitive networking (TSN) over wireless for deterministic data transmission

Time-Sensitive Networking, originally developed for wired Ethernet, aims to provide deterministic latency and guaranteed bandwidth for critical traffic. Extending TSN concepts over wireless links is an active area of research and standardisation, driven by the desire to support hard real-time industrial control over flexible radio networks. While full TSN-grade determinism over wireless is not yet commonplace, foundational elements such as time synchronisation, traffic scheduling, and priority queuing are increasingly integrated into emerging Wi‑Fi and 5G standards.

In practical terms, TSN over wireless seeks to ensure that control messages arrive within strict deadlines, even amid varying channel conditions and interference. Think of it as creating reserved lanes on a busy motorway: no matter how much general traffic there is, high-priority packets always have a clear path. This is crucial for applications such as coordinated motion control of multiple robots or synchronised drives in packaging and printing lines.

As vendors introduce TSN-capable access points, 5G base stations, and industrial controllers, you can expect hybrid topologies where wired TSN backbones extend to wireless “last-metre” segments. When evaluating these solutions, pay close attention to end-to-end latency budgets, clock synchronisation accuracy (for example, via IEEE 1588 PTP), and how well the wireless infrastructure integrates with existing TSN configuration and monitoring tools.

Wireless SCADA systems and remote terminal unit (RTU) communication architectures

Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems were among the earliest adopters of wireless communication in industry, especially in sectors such as water utilities, oil and gas pipelines, and electric power distribution. Today, wireless SCADA architectures continue to evolve, leveraging modern radio technologies to connect Remote Terminal Units (RTUs) and Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) over vast geographic areas. Instead of relying solely on leased lines or proprietary radio links, many operators now use a mix of licensed microwave, LTE/5G, and unlicensed point-to-multipoint radios.

In a typical wireless SCADA deployment, RTUs at remote sites collect process data—such as flow, pressure, and valve status—and transmit it to a central control centre at configurable intervals or upon alarm conditions. Communication can be event-driven, polled, or based on publish/subscribe patterns using protocols like DNP3, IEC 60870‑5‑104, or MQTT. Network design must account for limited bandwidth and higher latency compared to local control networks, which is why time-critical control loops usually remain local to the RTU, with SCADA focusing on supervision and optimisation.

Architecturally, redundancy and security are paramount. Dual radio links (for example, primary LTE with satellite or licensed microwave backup) help maintain connectivity during outages or extreme weather events. Encryption, authentication, and VPN tunnelling are essential to protect critical infrastructure from cyber threats, especially when public networks are involved. When planning or upgrading a wireless SCADA system, you should perform a detailed risk assessment covering coverage gaps, failover scenarios, and cyberattack vectors.

Electromagnetic interference mitigation and frequency spectrum management in industrial environments

Industrial facilities present some of the most challenging environments for wireless communication. High-power motors, variable frequency drives, welding equipment, and dense metal structures all contribute to electromagnetic interference and multipath propagation. Without careful planning, these factors can degrade signal quality, increase packet loss, and undermine the reliability of wireless industrial systems. Effective interference mitigation and spectrum management are therefore as important as selecting the right protocol.

Think of the radio spectrum on your site as a shared resource, much like compressed air or cooling water. If multiple systems compete for the same frequencies without coordination, performance will suffer across the board. Spectrum surveys, ongoing monitoring, and clear policies about which bands and channels are used by which applications are vital steps in preventing conflicts. Many organisations now treat spectrum management as a formal engineering discipline, with documented design rules, change-control procedures, and periodic audits.

Spread spectrum techniques: FHSS and DSSS for Noise-Resistant transmission

Spread spectrum techniques such as Frequency-Hopping Spread Spectrum (FHSS) and Direct-Sequence Spread Spectrum (DSSS) are foundational tools for combating interference in industrial wireless communication. FHSS rapidly switches the carrier frequency according to a pseudo-random sequence known to both transmitter and receiver. If interference or noise affects one frequency, the system spends only a brief moment there before hopping to a cleaner channel, improving resilience without requiring high transmit power.

DSSS, by contrast, spreads the signal over a wider frequency band by multiplying the data with a higher-rate pseudo-noise code. At the receiver, correlating with the same code reconstructs the original message while treating narrowband interference as relatively low-level noise. Many IEEE 802.15.4-based industrial protocols, including WirelessHART and ISA100.11a, use DSSS or hybrid techniques to achieve robust performance in cluttered spectrum.

When evaluating wireless platforms for industrial use, it is worth asking vendors how their implementations leverage FHSS, DSSS, or hybrid approaches. Not all spread spectrum systems are created equal, and parameters such as hop rate, channel set size, and processing gain can meaningfully influence performance under real-world interference. Laboratory tests and pilot deployments in representative environments are often the best way to validate claims and build confidence.

Coexistence strategies for multiple wireless protocols in shared 2.4 GHz and Sub-GHz bands

The 2.4 GHz ISM band is home to a crowded ecosystem of technologies: Wi‑Fi, Bluetooth, Zigbee, ISA100.11a, WirelessHART, and various proprietary systems all contend for limited spectrum. Similarly, sub‑GHz bands used by LoRaWAN, proprietary FHSS radios, and legacy telemetry systems must coexist without mutual disruption. Coexistence strategies aim to ensure that these diverse protocols can share frequencies with acceptable performance for all stakeholders.

Practical coexistence starts with band planning and channel allocation. For example, you might dedicate specific Wi‑Fi channels for office traffic while reserving others for industrial applications, or separate time-critical wireless sensor networks from high-throughput video streams. Many industrial protocols implement adaptive channel blacklisting and dynamic frequency selection to avoid persistently noisy channels, effectively steering traffic away from problem areas.

From an operational standpoint, cross-team communication is essential. IT and OT specialists should collaborate on a unified radio frequency plan, rather than deploying systems independently. Regular RF surveys can reveal evolving interference patterns as equipment is added or reconfigured. In some cases, moving a critical industrial application to a less crowded band—such as 5 GHz or 6 GHz for Wi‑Fi, or licensed spectrum for private LTE—can dramatically improve reliability.

Shielding and antenna placement guidelines for heavy machinery and metallic structures

Even the best wireless protocols and spectrum plans can be undermined by poor physical installation. Heavy machinery, structural steel, tanks, and pipe racks create reflections and shadowing that distort or block wireless signals. Proper antenna selection and placement are therefore crucial for creating reliable wireless links in plants and factories. As a rule of thumb, line-of-sight paths are preferable, but in practice you must design for a mix of direct and reflected paths.

Position antennas above major obstructions where possible, and avoid placing them directly behind metallic surfaces or within enclosures without suitable RF windows. In some cases, directional antennas can be used to focus energy along desired paths, reducing the impact of nearby interferers. For large indoor spaces, a distributed antenna system or additional repeaters may be needed to fill coverage gaps and provide redundant paths.

Shielding and grounding practices also play a role. Cables to remote antennas should be properly shielded and routed away from high-power conductors to minimise induced noise. When installing wireless equipment in outdoor or hazardous locations, choose enclosures and mounting hardware rated for the environment, but ensure that these do not excessively attenuate radio signals. Documenting and validating antenna layouts through site surveys helps you catch issues early, before they manifest as intermittent communication problems.

Cybersecurity frameworks for wireless industrial networks: IEC 62443 and zero trust architecture

As industrial wireless networks become more pervasive and critical, their attack surface inevitably expands. Cybersecurity can no longer be an afterthought; it must be embedded into every layer of design and operation. Frameworks such as IEC 62443 provide a comprehensive set of requirements and best practices for securing industrial automation and control systems, including wireless components. At the same time, the Zero Trust security model—“never trust, always verify”—is gaining traction as a pragmatic approach to protecting distributed, heterogeneous environments.

IEC 62443 encourages a defence-in-depth strategy, segmenting networks into security zones, defining conduits between them, and applying appropriate technical and organisational controls. Wireless networks often span multiple zones, connecting field devices, edge gateways, and enterprise services, which makes proper segmentation and access control especially important. Zero Trust principles complement this by insisting that every device, user, and data flow be authenticated, authorised, and continuously monitored, regardless of its location inside or outside the plant perimeter.

AES-256 encryption and secure boot mechanisms for wireless field devices

At the device level, strong cryptographic protections are essential to prevent eavesdropping, tampering, and impersonation. Many industrial wireless protocols already mandate AES-128 encryption, which remains secure for most use cases. However, an increasing number of vendors are adopting AES‑256 and more advanced key management schemes to align with corporate IT policies and emerging regulatory expectations. End-to-end encryption, where data remains protected from field device to application server, further reduces exposure to man-in-the-middle attacks.

Secure boot mechanisms ensure that wireless field devices and gateways run only authenticated firmware, verified using digital signatures stored in hardware-protected key stores. This prevents attackers from loading malicious code onto edge devices, which could otherwise serve as stepping stones into broader OT networks. Combined with secure firmware update processes—ideally supporting signed, encrypted over-the-air updates—you gain the ability to patch vulnerabilities promptly without compromising integrity.

When specifying wireless equipment, it is wise to request detailed security documentation: supported cipher suites, key lengths, certificate management options, and hardware security features such as Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs) or secure elements. This information allows you to align device capabilities with your organisation’s broader security architecture and compliance requirements.

Network segmentation and virtual LAN (VLAN) configuration for wireless access points

Proper network segmentation is one of the most effective ways to contain security incidents and limit lateral movement by attackers. In wireless industrial environments, segmentation is typically implemented using Virtual LANs (VLANs), access control lists (ACLs), and firewalls that separate control traffic from corporate IT, guest access, and non-critical services. Wireless access points and controllers should support multiple SSIDs mapped to distinct VLANs, with tailored security policies for each.

For example, you might create one VLAN for safety and control traffic from wireless sensors, another for maintenance laptops, and a third for visitors or contractors. Role-based access control can then be enforced at the network edge, ensuring that each device can reach only the resources it genuinely needs. Combining VLANs with technologies such as 802.1X authentication and Network Access Control (NAC) further strengthens your posture by verifying device identity and compliance posture before granting access.

From a practical standpoint, documenting your segmentation strategy and keeping configurations consistent across wired and wireless infrastructure are crucial. Misaligned VLAN tags, inconsistent ACLs, or unmanaged access points can create blind spots that attackers exploit. Regular configuration audits and automated compliance checks help maintain the intended security boundaries as your wireless footprint grows.

Intrusion detection systems (IDS) and anomaly detection in wireless industrial traffic

Even with strong preventive controls, it is prudent to assume that some threats will eventually bypass perimeter defences. Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) and anomaly detection tools provide the necessary visibility to detect suspicious activity in wireless industrial traffic before it leads to serious consequences. These systems analyse network flows, protocol behaviour, and sometimes even physical-layer characteristics to identify patterns indicative of scanning, spoofing, or command injection attacks.

In recent years, machine learning-based anomaly detection has become more prevalent, particularly for IIoT environments where normal traffic patterns can be highly regular. By learning what “normal” looks like for specific devices and processes, these systems can flag deviations such as unusual data volumes, unexpected command sequences, or connections to unfamiliar endpoints. When integrated with Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) platforms, such alerts support faster triage and incident response.

For best results, IDS and anomaly detection should be deployed in conjunction with robust logging, time synchronisation, and incident response playbooks. Wireless gateways and access points should export detailed telemetry, including failed authentication attempts, configuration changes, and radio-level statistics that may indicate jamming or spoofing attempts. Over time, this continuous monitoring becomes a powerful feedback loop, helping you refine security controls and harden your wireless industrial networks.

Predictive maintenance and digital twin integration through wireless vibration and thermal sensors

One of the most tangible benefits of wireless technology in advanced industrial systems is the enablement of predictive maintenance and digital twin strategies. By deploying wireless vibration and thermal sensors on critical assets—such as pumps, motors, gearboxes, and heat exchangers—you gain continuous visibility into their operating condition without installing extensive cabling. These sensors act as the eyes and ears of your maintenance programme, capturing subtle changes in behaviour that often precede failures.

Data from wireless sensors is streamed to edge analytics platforms or central condition monitoring systems, where algorithms detect patterns associated with bearing wear, imbalance, misalignment, or overheating. Instead of relying on fixed-interval inspections or reacting to breakdowns, you can schedule interventions at the optimal time, reducing unplanned downtime and extending asset life. According to various industry studies, well-executed predictive maintenance programmes can reduce maintenance costs by 10–40% and cut unplanned outages by up to 50%.

Digital twins take this concept a step further by creating virtual replicas of physical assets or entire production lines. These models ingest real-time sensor data—often over wireless links—to simulate performance, predict future degradation, and test “what-if” scenarios. For example, you might evaluate how a change in operating speed affects vibration levels before implementing it on the actual machine. Wireless connectivity makes it feasible to maintain digital twins for large fleets of assets, even in locations where running cables would be infeasible or too costly.

From an implementation perspective, success hinges on choosing the right sensing strategy and communication technologies. High-frequency vibration analysis may require higher bandwidth and lower latency than basic temperature trending, influencing whether you use Wi‑Fi, ISA100.11a, WirelessHART, or another technology. Battery life, environmental rating, and ease of installation are also key selection criteria. By aligning these technical decisions with clear business objectives—such as reducing specific failure modes or supporting a digital twin roadmap—you can unlock the full value of wireless-enabled predictive maintenance in your industrial operations.